On Versioning

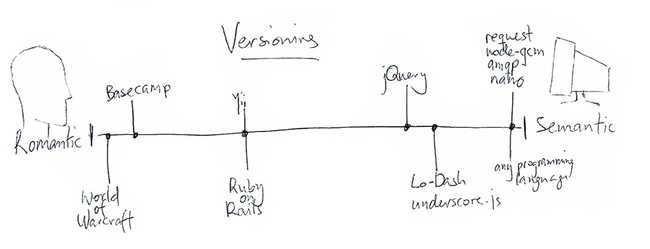

In a recent outburst on Twitter and Github, Jeremy Ashkensas and David Heinemeier Hansson argue for Romantic Versioning (versioning with heart) rather than Semantic Versioning (functionally meaningful versioning). I argue that the debate has been lacking nuance, and provide a model for deciding on how to version a given project.

Recently, Semantic Versioning has been the subject of much debate in software development circles, after a discussion about the versioning of underscore.js, a Javascript library providing functional paradigms, was brought to the masses by HackerNews and David Heinemeier Hansson.

Semantic Versioning is the idea that versioning should be functionally meaningful – that the different increments in version have a logical meaning: patch version bumps keep the current functionality and interfaces, but fixes an issue or solves a common problem; minor version bumps add new features without breaking backwards compatibility; and major version bumps introduce breaking changes.

Having a meaningful kind of versioning makes it possible to depend on automatic dependency updates (of minor and patch updates). There is no need to go through the dependencies manually, and read all the changelogs.

The discussion started when underscore.js introduced breaking changes with a minor version bump (1.7.0). underscore.js never claimed to follow semantic versioning, but the node package manager environment, in which it is the most depended-on software package, generally expects this convention. The result was that a lot of packages became immediately unusable. They depended on underscore.js, updating minor versions automatically, and suffered under the breaking changes.

The attention pointed at this whole thing prompted Jeremy Ashkenas, the man behind underscore.js, to write a small essay of sorts discussing versioning, and ultimately arguing against semantic versioning. He offers an alternative, which he calls Romantic Versioning. In romantic versioning, the main factor in deciding the version bump for a change is linguistics: does it feel major, minor or is it just a patch? Romantic versioning is focused much more on subjective opinions about the size of a change, emphasizing that version numbers should be human readable, letting the functionally meaningful part take a back seat.

Ashkensas argues that “SemVer tries to compress a huge amount of information […] into a single number. And unsurprisingly, it’s impossible for that single number to contain enough meaningful information,” calling it a “false promise” of “pain-free […] dependencies”.

Hansson backs him up, calling SemVer a “fundamentalistic approach to software versioning that eschews all nuance in a vain search of consistency,” arguing that “Software versioning and releases are as much about confidence, communication, and community as about a technical declaration of goods.”

There are a lot of people who disagree with this sentiment, because they want software that doesn’t break when updates are made to dependencies. Of course, it is very easy to waft these ideas away, by way of the arguments provided above, and the debate quick came to a halt, each side sticking to their guns.

Nuance #

I think the discussion has had a tendency of generalization to it, which hasn’t been healthy. There are nuances to everything, and this discussion is definitely not excluded. There are different sizes and contexts of software projects, and different kinds call for different standards.

I would argue that standards for versioning should be chosen based on the interface of the project they are describing. It is clear that SemVer shares this idea (although not in a way that is as nuanced as what I will present below), as they care about how the interface changes: does it break? does it become bigger? does it stay the same?

World of Warcraft is an MMORPG, a video game. It is quite far from what is usually considered in discussions about software development, and even more so when discussing the merits of different kinds of versioning. But it is software, and it has an interface just like any other piece software. World of Warcraft’s interface is to the user, the outermost layer, the game experience.

So how do they version the game? Patches are mostly hotfixes, minor version bumps add new content, and major version bumps are new, paid expansions. [1] The only external interface they have to keep is to the user, so any “breakage” is in human interaction. They do not actually run a risk of making the game unplayable, as people automatically adapt. Because talking about breaking the interface is irrelevant they use minor versions to signify medium-sized additions and a few changes in content, and major versions to signify big additions and big changes in content.

Basecamp has only ever seen two major versions: Basecamp and Basecamp 2. Here, the major version was a significant revamp of the core concept; a completely new piece of software. This makes clear what is slightly harder to see in the case of World of Warcraft: when the interface of a piece of software is towards the user, the versioning should be user-centric.

Users are historically used to slower software releases, and expect something substantial when the sequel is released. This doesn’t mean you should limit your rate of new development, but it means that you should not update the major version for a tiny interface change (however technically breaking it may be).

As an aside, it is also worth considering that releasing a new major version of human-focused software will often give the customers reason to consider whether they should change to a different product altogether. After all, a new major version is a big change; maybe there is a different big change that works better for them. Releasing a major version without convincing arguments for adopting it is dangerous.

Ruby on Rails is a framework for web development, which has been known to introduce (very few) breaking changes in non-major releases. Most changes to interfaces in minor versions are in the form of deprecations of newly discouraged methods.

In this case, the audience is not only people, it is also programs: there are web apps running in the framework that may use some of the functionality which changes its interface.

A web app does not update its framework version as often as it updates individual tools. A framework update (no matter how small) entails a change in how the app is developed. There will be new things to adapt to, new ways of doing things. Patch updates are still generally considered non-breaking and should be applied as they often close holes in security. Other than that, each update is considered carefully by the web app developers, and this explains the versioning model of Ruby on Rails.

Lo-Dash (a fork of underscore.js) provides constructs known from functional programming to Javascript, but also provides new syntax (unlike regular Javascript). It places itself somewhere between a framework and a tool library: it dictates, to some extent, how code is written, but is ultimately used for minor operations (like mapping, reducing, filtering). It will not permeate the entire system, but the parts that use it will very clearly be “lodash-code” (or “underscore-code”).

Lo-Dash is a tool-library, so updates will quickly be adopted by other systems, sometimes automatically. Lo-Dash uses strict semantic versioning, which is the pragmatically most useful solution. There are very few users who will actually look at (and care about) the version of a library like this. They will not be disappointed if there aren’t enough new features in the next major version.

nano is a library for accessing CouchDb databases. It is very much a pure tool: it is not a framework, it follows regular Javascript syntax, and it is targeted wholly at developers. nano is (at the time of writing) in version 6.0.2, and follows semantic versioning. Users will not have a relationship to the versioning of a library like this, and only the vanity of the author would ever keep a tool from using functionally meaningful versioning.

The gist #

I have mentioned five projects that, in my opinion, use versioning reasonably. I think these examples should be looked to when in doubt, and the mode of versioning of each project can easily be applied to similar projects.

Instead of World of Warcraft I could have talked about any other game, instead of Basecamp I could have mentioned any other web app, instead of Ruby on Rails I could have mentioned any other web framework, instead of underscore.js I could have mentioned jQuery or other similar libraries, and instead of nano I could have mentioned any of the plethora of other small tool-libraries out there.

I found the original discussion overly generalized and lacking in nuance. I have tried to paint the image of a gradient: In truth, software ranges from that with interfaces focused directly on users to that which is focused only on other applications.

On this gradient, we find underscore.js close to the end that would benefit from having functionally meaningful versioning, and as such I think the decision to use romantic versioning was wrong.

Notes #

Thanks to Morten Brix Pedersen for reading early versions of this blog post, and providing invaluable critique.

I mentioned the following systems (in order of appearance): underscore.js, Basecamp, Ruby on Rails, World of Warcraft, Lo-Dash, nano, and CouchDB.

[1] A list of all of the the World of Warcraft patches is available on WoWWiki.